I touched upon this issue briefly in my video, but I felt a more detailed explanation was necessary.

One of the reasons why you’ve been conditioned to underachieve in your maths exams is due to advice given by your peers and teachers. Us human beings have a tendency to imitate what others around us are doing. We see somebody or hear about somebody writing notes from a revision guide and we feel it’s the right thing to do. However, if somebody else is doing it, it doesn’t mean it’s the right thing to do. It’s kind of like the ‘if he/she jumped off a bridge, would you?’ Writing notes from a revision guide is one of the most inefficient activities you can do during revision. When you’re revising, you have to weigh up activity against time. Time is your most valuable asset and you cannot afford to waste it on activities that will not directly improve your grades.

The reason why note-taking is impractical is because you won’t remember everything you’ve written down on the first occasion. You could spend hours writing notes on a few chapters from a revision guide yet you’ll only retain 10% of what you’ve just written. It’s only when you revisit those chapters several times and make additional notes, it begins to stick. You’re probably experiencing this right now in your revision. Thus, note-taking is not a good memory retention tool from the outset (and remember, one of the key ingredients for exam success is memory!) In my revision program, I flip the typical revision process on it’s head. I advise my students to write notes at the end, just days/weeks before an exam. You may think we’re leaving it too late but believe me, this is when note-taking is at it’s most effective.

You’re conditioned to underachieve in your maths from an early age; as soon as you begin year 4/5. This is because the school divides the year group into sets of varying ability. For instance, the high attaining students are in the top set, average attaining students are in the middle sets and low attaining students are in the bottom set.

China, on the other hand, don’t believe in this philosophy. Their classes hold up to 50 students of mixed ability. I agree with this approach because it places everybody on a equal footing. Views such as “I’m in a lower set so I can’t achieve an A grade” do not exist. Instead, every student is pushed to achieve the best grades. That is why Chinese students do exceptionally well in their studies in comparison to British students. As a matter of fact, when Chinese students reach 16 years of age, they are already 3 years ahead of their British counterparts.

An experiment was carried out in Bohunt School (Hampshire) recently to see if the Chinese way of teaching would outperform the British set-up. You may have seen it on TV. The programme was called ‘Are Our Kids Tough Enough?’ and it featured on BBC Two. Five Chinese teachers took over a class of 50 year 9 students for four weeks. When the results were released, the Chinese teachers won by a clear distance.

Segmenting students based on ability is a dangerous thing to do because if you happen to fall into one of the average/low achieving sets, they’re instilling the belief in you that you’re ‘just an average achieving student’. By setting you lower level work and assessments, it’s difficult for you to strive for the best grades. After a while, you are convinced that this is the level you should be working at and the best grades are simply out of your reach. This belief stays with you throughout your school life and as a result, you only achieve mediocre grades such as B’s, C’s and D’s. Mediocre grades will seriously jeopardise your career prospects in the future.

This doesn’t happen to everybody, however. In rare cases, the student can overcome this perceived view about their ability. I was an example of this. At school, teachers used to say repeatedly that I wasn’t working hard enough (I’ll come to this in a minute) and I would underachieve in my maths exams but I never let this go to my head. I was confident in my ability and I ‘knew’ I was going to score top grades. This is because I understood the revision process really well. I knew what activities would directly improve my grades and which ones didn’t. There were students in my class who worked around-the-clock yet still underachieved in their exams and there was me who put in half the amount of effort and scored very good grades.

It’s crucial to have a positive outlook on your studies. Don’t let the predictions of others or teachers get the better of you. As soon as it does, you’ve already lost the revision battle and you might as well give up. Always strive for the best results because it’s not impossible. You just have to be focused, consistent and put in a bit of concentrated effort when it’s required. There was a student at my university who had failed his GCSE maths in the past. However, with a shift in mindset, he was able to score A/A* in his GCSE and A-level maths, and then study the subject at a top 10 university in the UK. This proves that you can achieve any grade you desire as long as you have a positive attitude and the right revision tools at your disposal.

A misconception held by the majority of students is that you have to work hard to get the best results. There is a common notion that the more you work, the better the results. However, the opposite is true. You can work less and score better grades providing that you focus solely on the the more important areas of your revision. Have you heard of Pareto’s law? Pareto was an Italian economist and he said that 80% of your results come from only 20% of your activities. This is a universal law and can be applied to revision and taking exams. Only 20% of what you do in your revision will contribute to 80% of your grades in the end. Do you ever wonder how some students can revise ‘last minute’ or days before an exam and still score a good grade? It’s because they’re focusing on just this 20% of activities in the run up to their exam.

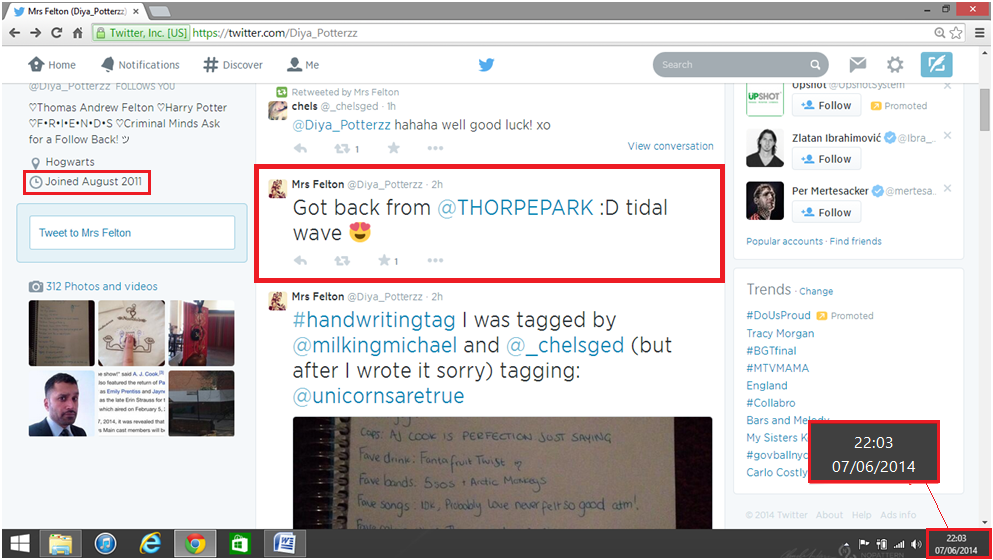

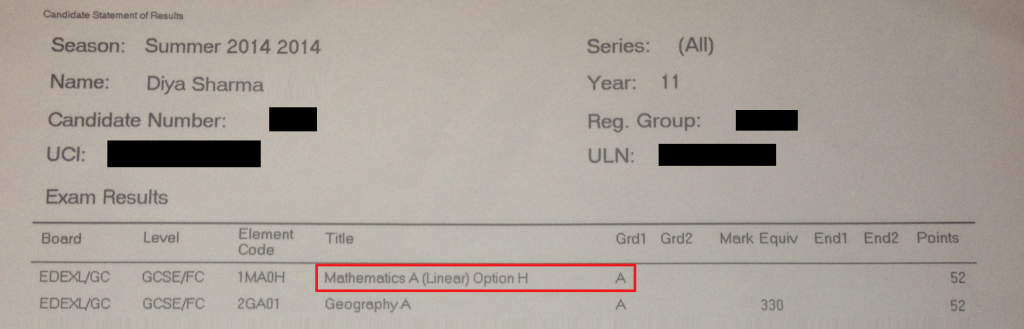

Diya, an ex-student of ours, understood this 80/20 rule really well and this allowed her to go to Thorpe Park just 2 days before her final maths exam. It didn’t affect her at all because up to this point, she’d followed all of my revision principles. In the end, she still scored a solid ‘A’ grade (up from a C). Proof of this is given below. This is her tweet posted on the 7th June 2014 (her final exam was on the 9th June 2014):

My revision program abides by this 80/20 rule. What I’ve done, in my program, is removed the activities that will not directly contribute to your end result such as writing copious notes and focuses on activities that will. You just simply have to follow everything I’ve set out in the program and results will drastically improve. It’s important that you follow this program, not only because it will boost your results in the long run but it’s good for your mental and physical well being too. It is unnatural for human beings to barricade themselves in a room, sit at a desk and write notes from a textbook. I strongly advise against this. You still need to mix with your peers and stay active. I used to do this myself during exams and I still achieved the top grades so there is no reason why you can’t do it too.